Gradients

What is a gradient?

The word gradient comes from the Latin root gradus, meaning “a step towards, or a step climbed on a ladder or stair.” Biologists are very interested in climatic gradients—places where the environment changes in a measurable and predictable way as you move in a particular direction. For instance, average temperatures gradually fall and average precipitation and wind speeds rise as you travel upwards on an elevational gradient, such as a mountain. Similarly, we see dramatic shifts in climate along latitudinal gradients—lines running between the Earth’s north and south poles—with equatorial locations being much warmer and having much longer growing seasons than those closer to the poles.

It can be difficult, time consuming, and expensive to conduct laboratory experiments that directly manipulate climatic variables and test how organisms respond. That’s why natural gradients are so valuable. Observing species where they naturally occur at different locations along a climatic gradient provides insight into how their distributions, behavior, physiology, or genetics are affected by environmental conditions. To do this, biologists often set up an elevational or latitudinal transect—a series of study sites located at approximately equal distances apart along a gradient. Data collected from a transect can then be used to try to predict how organisms will respond to future climate change. In fact, this is often called a “space for time substitution” approach, because instead of conducting a study that stretches out for a long period of time, we can conduct one that stretches out over a large space, and by doing so allows us to “look into the future.”

For example, if we find that the abundance of various plant species is different at different sites on a transect, that suggests something about the ideal environmental conditions for each species, as well as the limits of the conditions it can tolerate. If conditions change, one thing species might do is shift their geographical distribution to track, or follow, their ideal climate. By comparing climate data with species abundance data, we can build a statistical model that predicts where each species will be distributed in the future.

Ecology and evolution along gradients

The case studies on this website involve data collected on invertebrates living along both elevational and latitudinal gradients: grasshoppers in Colorado and butterflies in Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and the Canadian Rocky Mountains. It’s worth taking a moment to consider several characteristics that are common to the ecology and evolution of species living along environmental gradients. Remember that gradients are directional; that is, conditions don’t change randomly as you move along them, but tend to increase or decrease continuously. Therefore, opposite ends of a gradient are: 1) extremely different from each other, and 2) where we find relatively extreme environmental conditions. For this reason, we often see different fitness constraints affecting individuals living at opposite ends of a gradient. (Biologically, fitness refers to the ability of an organism to reproduce and pass on its genes to the next generation, and since no individual can have an infinite number of offspring, a constraint is anything that limits this ability.)

At low elevations on a mountain, for example, where daily temperatures are the warmest and the growing season is the longest, competition with other species for food and other resources may place the strongest constraint on fitness. In contrast, insufficient warmth and a very short season for growth and reproduction may be the biggest fitness constraints at high elevations. These differences affect how these populations evolve, because natural selection will favor different traits for each population— at low elevations, individuals that are better competitors will pass on more of their genes, while at high elevations, the same will be true of individuals that require the least resources to reproduce. For example, the same species of alpine plant may produce larger flowers in lower elevation meadows, because showy blooms attract pollinators away from competing plants. In meadows located at the highest elevations, smaller flowers may be more favorable because they can develop more quickly, and be pollinated in time for fruit and seeds to mature before the season ends.

If these phenotypic differences are the result of evolutionary change, meaning they come from differences in genetics, we describe these populations as being locally adapted. That is, the effects of natural selection have led to them becoming more well-suited to the specific (local) environmental conditions where they are found. You might imagine that any population experiencing a specific set of pressures from natural selection should eventually become locally adapted, but this can only happen if gene flow among populations is limited. Gene flow occurs whenever individuals, or the genes they carry, move between populations—like an adult butterfly laying eggs at a different location from where it emerged as a caterpillar, or a seed being blown on the wind to a different location from where its parent plant was rooted. When new genes arrive in a population, they change its genetic makeup. This can be beneficial; greater genetic variation contributes to the population’s ability to adapt to future changes, by increasing the chances that it holds alleles coding for traits that are suitable for different conditions. However, genes flowing in from elsewhere can also “drown out” those of local inhabitants, making it less likely for local adaptation to occur.

Differences among populations along a gradient can also be due to plasticity rather than genetic changes. Plasticity refers to organisms with the same genetic makeup displaying different phenotypes depending on the environment in which they live; this name comes from the idea that plastic substances can be molded into many different shapes. Often, the conditions an individual is exposed to as it is maturing (e.g. from an egg to a larva or a larva to an adult) can influence the way its phenotype develops. We call this developmental plasticity. Individuals that are highly plastic can respond well to short-term environmental changes, but these responses cannot then be passed down to their offspring. (In general, high-elevation populations of a species tend to be more plastic than low-elevation populations, to allow them to survive and reproduce in the more variable conditions that occur near mountain peaks.

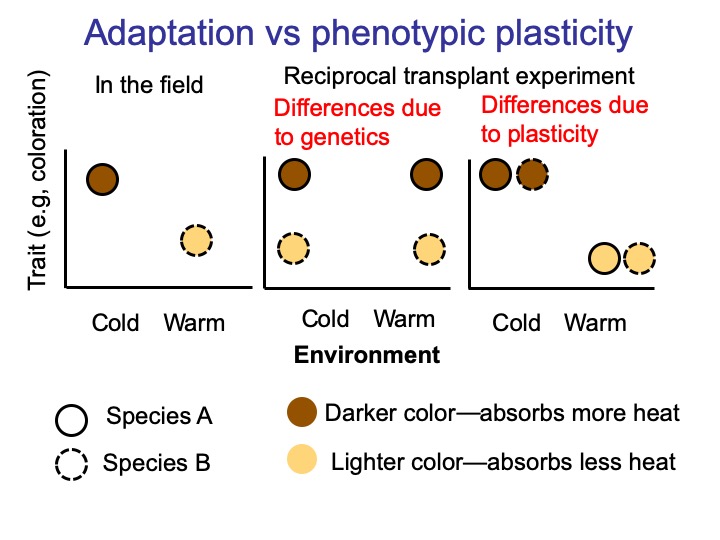

The figure below shows how we can tell the difference between adaptation and plasticity using a reciprocal transplant: an experiment where individuals of the same species from two populations (e.g. cold vs. warm habitats) are collected from the field and then transplanted into the opposite habitat. If the differences between them are due to adaptation, we would expect the transplanted individuals to behave the same as they do in their home location, but if the differences are due to plasticity, we expect to see a shift to the opposite phenotype once they’re transplanted.

Coping with climate change

The history of gene flow and local adaptation in a given population, as well as its degree of phenotypic plasticity, will all affect its ability to thrive under new conditions. That’s because these forces interact in complex ways to determine how a species living along an environmental gradient will respond to climate change. For example, plasticity can allow individuals to survive under less than optimal conditions, but slow down the process of adaptation to these new conditions.

Researchers led by ecologist Lauren Buckley and Joseph Ehrenberger investigated the impact of behavioral plasticity in a North American lizard species (Yes, behaviors are phenotypic traits!). In this case, what is “plastic” is how these Eastern Fence Lizards behave in response to changes in temperature. Instead of allowing their body temperatures to be dictated by their surroundings, they shuttle between sunny and shady areas all day, keeping their internal body temperatures relatively constant. This strategy is known as behavioral thermoregulation. Thermoregulation is very important for these lizards, because temperature has such a powerful influence on physiological functions like metabolism in ectotherms. But it may ultimately leave them more vulnerable to climate change. Key here is the idea that because behavioral plasticity currently allows most lizards to survive and reproduce under a range of conditions, there isn’t strong selection for lizards whose genes make them more robust against extremely high temperatures. And we know that extreme temperature spikes are going to become much more common in the future. When that happens, these lizards’ reliance on plasticity may ultimately mean they haven’t adapted fast enough.